I’ve been tracking the shape of grief since the first nightmare months after my son Noah’s suicide in 2013. The intensity of traumatic grief once filled every moment. The core of my identity, relationships, and activities was being a suicide loss survivor. Over 11 years, grief has gradually receded from the forefront. It takes up less space in my heart and mind and daily life. This has opened up space for new emotions, experiences, and purpose while still mourning my child.

I’ve been tracking the shape of grief since the first nightmare months after my son Noah’s suicide in 2013. The intensity of traumatic grief once filled every moment. The core of my identity, relationships, and activities was being a suicide loss survivor. Over 11 years, grief has gradually receded from the forefront. It takes up less space in my heart and mind and daily life. This has opened up space for new emotions, experiences, and purpose while still mourning my child.

How did this shift happen? I’m honored to visit this excellent blog to reflect on my grief process and offer hope to other bereaved families.

Noah was one of those full-of-life guys with many friends, interests, and talents who hid his troubles. He struggled with depression and anxiety after the suicide of a friend and found little help in treatment. While home from college on medical leave, two days after running the L.A. Marathon, he took his life. He was 21.

In the first few years after Noah’s suicide, I saw everything through the agonizing lens of grief. Every line from a song, every intention for a meditation reminded me of the shock and pain. The world was a hotbed of triggers, from gruesome Halloween decorations to intact families at a restaurant. I found signs of Noah everywhere, in rainbows, hummingbirds, oceans.

I was immersed in—sometimes swamped by—what psychologists call a “loss orientation,” focused on mourning. Moving toward a “restoration orientation” that allowed me to re-engage in life wasn’t quick, linear, or finite. It took the balm of time, but also lots of work and support.

When you lose someone to suicide, you call on everything you have to survive. I was lucky to have family, friends, community, and spiritual practices that grounded me. I had access to traditional therapy, mind-body approaches like EMDR, and support groups for suicide loss survivors. My oldest friend was a social worker who accompanied every step of my journey with love and wisdom. All these were lifelines that allowed me to move through grief at my own pace, back and forth between loss and restoration orientations, without pressure to “heal” quickly.

It also helped that I was well-acquainted with grief from losing my parents in my 20s and from researching laments and mourning customs in a Greek village when I was a grad student. So I wasn’t afraid of death, and I was inclined to express grief openly.

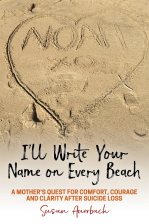

I was also inclined to write my way through tough emotions. After scrawling incoherent cries in my journal, I began blogging out of a fierce need to order my thoughts, tell my story, and recover my agency. The suicide made me feel small, silenced, betrayed. It shattered my dreams for my child and everything I believed about life and relationships. A key to healing after suicide is rebuilding those “assumptive worlds” of trust and belief, says Dr. Jack Jordan. I started doing that work on the blog, in a grief memoir, and in outreach to fellow survivors.

Meanwhile, I lamented Noah through poetry, finding comfort in speaking directly to him through elegies. As in this excerpt from “Tending the Shrine, Two Years On,” in my new poetry book:

I dust your album and open

to a boy with a handful

of grasshopper, a grinning teen

atop a sailboat mast, then

a student home for winter break,

gaunt and haunted as a refugee.

When did the end begin?

Like a scrim it shades

every picture,

each moment captured

nearly eclipsed.

The more I bore witness on the page, the more I noticed shifts in my grieving. Like when I made it through a day without crying or woke up breathing deeply. Or when I could list the good things I did to counter my long rap sheet of should-have/could-haves. Gradually, I could face holidays like Mother’s Day or Passover with less dread. Slowly, gratitude, joy, and faith crept back in.

Experts say that exploring one’s grief and ruminating on traumatic loss can open the way to “post-traumatic growth” with new relationships, strength, and purpose. Though I scoffed at this idea in the early years, eventually it made sense. I realized I’d become more attuned to and compassionate toward others’ suffering. I was giving full attention to my living son, Ben, and deepening our connection. I’d sought out suicide prevention training and added that messaging to public speaking about Noah and my book. I dreamed of publishing a collection of grief poetry to honor Noah.

By ten years after the suicide, I was more focused on intentional remembering than on intentional mourning. My husband and I made a round of visits to Noah’s friends to share memories. I wrote love notes to everyone who’d been part of the circle of care after the suicide. I decided to make marking Noah’s birthday a bigger deal than his death anniversary.

Suicide loss has shaped me in many ways, but it no longer defines me. Grief waves still come, though less often and less intensely; I let them wash over me and feel closer to Noah. I still write elegies to him, like “Ripped” (below). But lately, my poems have been venturing beyond the key of grief into new tonalities.

I’m letting myself be happy when I feel happy, despite being the mother of a suicide. The pain of losing Noah, once so piercing, has become an ache that flares and fades. I carry him with me always.

Ripped

Between the unmanned

lifeguard stations

surfers drift and bob like seals

in the swell. Big red lifeboats

lie beached on their sides.

I used to drive you here early

Sundays, after the donut shop,

before the taco place. You

suiting up behind the van

(that rip in the shoulder we never fixed),

eyeing older surfers with cool

nods, trotting fleet-footed

across the sand; me straining

to spot your lean torso in the lineup.

Once the fog was so thick I lost

sight of you before you reached

the break—weak with fear

thank God

you got out quick.

I never saw you catch a wave. Maybe

I missed it. Maybe it was enough

to paddle out and float inside

that briny vast embrace, lulled

by the brightening horizon.

Driving solo five years later,

you came back to claim

that peace, any peace,

but found it

gone.

You got out

quick.

Now I write your name on every beach,

scan the waves for your wake.

To my fellow survivors: Every path through traumatic grief is unique. I hope you can be with your grief, seek support, practice self-care, and open to growth. You might revisit these questions from John Schneider to notice shifts over time: “What is lost? What is left? What is possible?” Wishing you hope and healing.

© 2024 Susan Auerbach. Essay written for Speaking of Suicide.

Dear Susan,

Four years ago my divorce was finalized and I noticed very quickly that three of my four children began avoiding me. Then, after spewing some awful words at me, they went silent. No text or phone call on Mother’s Day, my birthday, Thanksgiving or Christmas. They went to their stepfather’s house instead. I heard about it from my one daughter who remained loyal. It felt like an unbearable “loss” but the loved ones I grieved were also actively torturing me. There were no graves to visit. Just phone calls from my siblings asking me did I know that my youngest one was engaged. My only son had a baby on the way. Did I know that the middle child was engaged in a same sex relationship.

I shut the world out. Had nothing to say that sounded remotely human. I could hear the groans from my groin where I birthed them but there was no one to talk to. I was hospitalized twice.

I did eventually find a website for rejected parents of adult children. I went back to school and studied creative writing. Got my MFA in poetry. Read a lot of wonderful work to witness the depths of human outcry. But this morning I read your webpage after reading the daily Rattle poem. Your photos and poems are lovely. Thank you for sharing.

With love and the utmost respect for your journey,

Meg